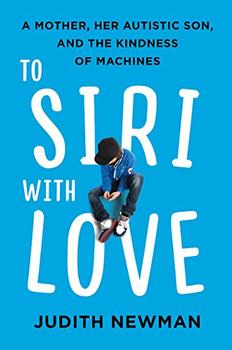

A book has just been published, entitled To Siri, With Love. The author is Judith Newman—a person we in the neurodivergent community call an “autism mommy”: that is, the non-autistic mother of an autistic child.

Ms. Newman is a great example of how neruodivergent points of view are commonly discounted, ignored, and subverted. Since neurodivergent people, by definition, think and see the world differently than the mainstream, we’re misunderstood. It’s like we’re speaking a different language, or like we come from a culture where all the gestures are different. Like, when I was in Nicaragua, and the “come hither” gesture looked to me like waving hello. Until I learned, every time someone told me to “come here”, I waved back…I wasn’t being nonsensical or thoughtless, I just had a different way of communicating.

This is how neurodivergent people feel, day in and day out. Since we don’t do or say the things people expect us to, they think we’re nonsensical, delusional, or thoughtless. This can lead our imprisonment, abuse, you name it. Because people don’t understand us, they think we’re dangerous, or unintelligent, or that our brains are “dead”. They think our lives aren’t worth living, and they treat us accordingly.

The author of To Siri, With Love is a perfect example of this mindset. Ms. Newman has stated that she doesn’t believe her son is capable of independent thought, or understanding others’ feelings. She publicly mocked his sexuality, telling the world what kind of porn he likes, and indicating she found the idea of him ever attempting sex to be silly and grotesque. This mother has stated outright, with impunity, that she doesn’t believe any girl[sic] will ever be interested in someone like him, and is planning to get a medical power of attorney so she can have him forcibly sterilized when he turns eighteen—because, in her words, “he can never be a real father.”

It probably comes as no surprise that the autism community is really scared, hurt and angry that this book has been published. It’s my understanding that the author has received death threats. I don’t agree with this, but that’s a view of how deeply the community is rattled. (If you want to see the quotes from the books and interviews, and community responses, check out the #BoycottToSiri hashtag on Twitter. Here is the thread of an activist who was included (and made fun of) in the book, without her permission, and here is my friend Kaelan Rhywol, live-tweeting her review of the book.

Full disclosure: I haven’t read this book yet. = I plan to, when I can get it at the library (I don’t want the author to have any of my money, or for her rankings to increase). [UPDATE: I’ve started reading it. Here’s my ongoing thread of tweets. I’ll be doing a full review when I’m done.] I feel the need to read it—even though chances are I’ll hate it—not only because her son sounds wonderful and I want to read about him, but because I want review the book, and I don’t review books I haven’t read. Rarely, I’ll review books I can’t finish, to be clear, but I never base a review on someone else’s opinion. They’ve already left that opinion, and if I can’t offer something new, there’s no point in saying anything.

However, in the case of this particular book, I wanted to review and speak out against its whole concept, and to things the author and her supporters have said and done, before I even deal with the particularities of the book. I think it’s important for me (and every other autistic person who can, and wants to) to make our voices heard on matters like these. Because allowing nothing about us without us is the only way neurodivergent people will ever gain their civil rights in this society. We need to show the world that we are thinking, feeling, intelligent individuals…because people literally think we aren’t, and that we shouldn’t have control over our own lives or narratives. Judith Newman is one of those people, and her viewpoint is popular enough that Harper Collins gave her a platform.

So, it’s time for me to dust of the old blogging fingers and write about one of my areas of expertise: points of view.

For those of you new to this blog, I’m a neurodivergent person. That means, my brain function is different than an average person’s. I am bipolar, autistic, and have PTSD. It’s caused me a lot of trouble and anguish in life, but it’s also pretty cool in other ways.

The first time I learned about point of view was when I had my first psychotic break, when I was about 14. I was wandering down the street screaming that I’d been poisoned and that I needed help. I wandered into a stranger’s house. They called the police.

Technically, I was breaking and entering (I didn’t actually break anything, I don’t believe, but still). Luckily, I wasn’t charged with it, because of the kindness of the police officer. But, from their point of view, I was a dangerous person.

I wasn’t dangerous. I was scared, and very upset.

Whose point of view was correct?

I can’t blame those people for being scared. They had no idea what was going on. However, if they’d been more knowledgeable about neurodivergence, they might not have been scared. They might have been able to offer me kindness and compassion, get me calmed down, and get me the help I needed. It would have been a less horrifying experience for all of us.

I still experience these divergence of points of view almost every day, even when I’m not in a psychotic break. For instance, I’ve been having a lot of problems with people shooting their guns on and near our property—hunting coyotes for the most part. This is a pretty heavily-populated area, all private property and it’s not legal to hunt here. The hunters’ bullets go astray, hit our outbuildings, scare the fuck out of my dog, my kid, and me. I went to my local Facebook group and posted a story of a woman in Wisconsin or somewhere who had been killed by just such an illegal hunter, and asked that people be more responsible with their guns.

Of course, cue a bunch of hunters to get pissed and tell me not to knock hunting.

When they said that, I freaked. The fuck. Out. They were basically saying it was okay to shoot at my house. I tried to reiterate the fact that it was illegal and wrong to hunt on my private property, or on other private property marked “NO HUNTING”, and have their bullets go astray and endanger my family and animals, but mostly I just called people idiots and pieces of shit.

I felt very threatened, is why.

I got banned, of course.

When I calmed down, I was able to see their point of view. They for the most part weren’t being directly threatening, they’d just—for no particular reason—thought I was bashing ALL hunters. And I had—wrongly, except for in the case of one commenter—felt like they were personally threatening me. Since I’m neurodivergent, (I have PTSD, and have had guns pulled on me, have been personally threatened with them), the way I felt and expressed my fear and anger was socially unacceptable. I’m working on it, but it’s difficult to control my reactions sometimes.

But, even if how I expressed myself was “wrong”, my fear and anger were understandable, right? All I wanted was for people not to shoot at my house, and for this, people called me “ignorant”. They said “People probably just don’t like you, libtard. That’s why they’re shooting at your house.”

Understandable or not, since I’m the neurodivergent one, I was immediately seen as the one being threatening. I was in the wrong, by mainstream standards.

The difference is, afterward, I can see where I went wrong. Those neurotypical people, in my experience, never will. I’m forced to live in their idea of mainstream reality, so I’m forced to constantly second-guess my point of view. They’re never forced to.

That’s neurotypical privilege: the privilege of living in mainstream reality, so to speak, and the ability to communicate one’s thoughts and feelings in mainstream ways.

The privilege of being, and feeling, “right”.

I see this type of divergence of point of view play out every day, in all aspects of life. Two completely different viewpoints, and each is completely unable to see the other’s. This happens between neurotypical folks, too, but it’s particularly bad for neurodivergent people, because—by nature—we think differently, and neurotypical people think our brains are wrong and defective.

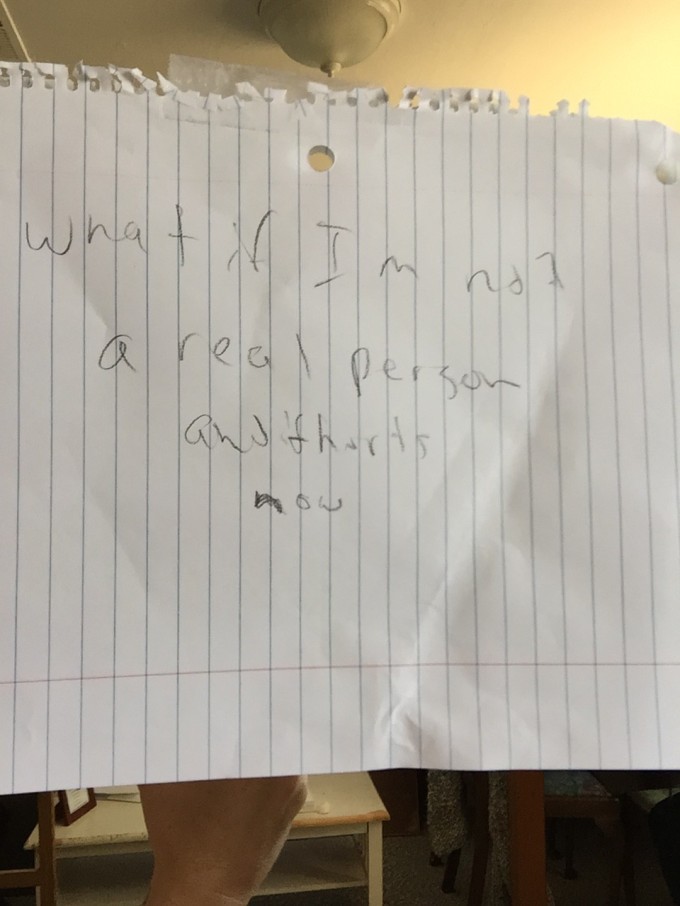

Can you imagine what it would be like if people thought your brain was wrong and defective? If they immediately dismissed everything you said, always misinterpreted you, and misunderstood you to the point of becoming angry or even violent, when you had no idea what you were doing wrong? Can you imagine if your own mother was like that?

This is how Judith Newman treats her son Gus. It’s the treatment she describes in the book.

I believe it, because this is what it is like for neurodivergent people, every day.

That guy ranting on the street corner (or the girl wandering down the street, screaming about spirits and poison, or the woman freaking out and calling you an idiot on Facebook)—in our own mind, we make sense, just as much as you make sense to yourself. If you got to know us fully, we’d make sense even to you.

We are sentient beings, and have fully-formed minds, just like you.

But hardly anyone wants to get to know “people like that”—people like me, or like Gus—because they think we’re dangerous, or at the very least, pathetic and annoying.

The woman who wrote To Siri, With Love, states throughout the book how annoying and nonsensical her son is—she’s being lauded by neurotypical culture for her “honesty”.

The autistic community, however, isn’t. We’re crying out to her that her son isn’t thoughtless or unlovable; that we’re like him; that often our mothers also thought we were incapable of love or thought, but here we are: thinking, functioning, feeling human beings, some of us with careers and families, all of us with loves and interests and inner lives.

But the author and her supporters are incapable of seeing that point of view. The author sees the outcry in the autistic community as bullying. She can only see her own hurt feelings, and can’t see that she has hurt the feelings of thousands of others…including her own son (whom she states in the book did not give his permission to be used in this way, or have his private life mocked and outed. The mother states that she didn’t think he was capable of consent).

Everyone who is reading this: I hope you will recognize that her point of view is wrong, even though it is currently the mainstream one.

It is time to change your way of thinking about neurodivergent people. It is time for our point of view to come into its own.

Elizabeth Roderick is an author and freelance editor. She thinks trains are pretty cool, and wouldn’t mind if one played percussion in her band. You can find her on Amazon, and on TalesFromPurgatory.com

Right now, President Trump, a Florida Sheriff, and millions of citizens are talking about how involuntarily locking up mentally ill/neurodivergent people is the answer to the U.S.’s gun violence problems. According to them, corralling all the “savage sickos” in hastily-erected, for-profit hospitals is in everyone’s best interests. Registering and rounding up neurodivergent people is much more practical and desirable than registering or confiscating people’s guns; Second Amendment freedoms apparently are more valuable than Fourth Amendment freedoms.

Right now, President Trump, a Florida Sheriff, and millions of citizens are talking about how involuntarily locking up mentally ill/neurodivergent people is the answer to the U.S.’s gun violence problems. According to them, corralling all the “savage sickos” in hastily-erected, for-profit hospitals is in everyone’s best interests. Registering and rounding up neurodivergent people is much more practical and desirable than registering or confiscating people’s guns; Second Amendment freedoms apparently are more valuable than Fourth Amendment freedoms. (revisiting this post from 2015)

(revisiting this post from 2015)

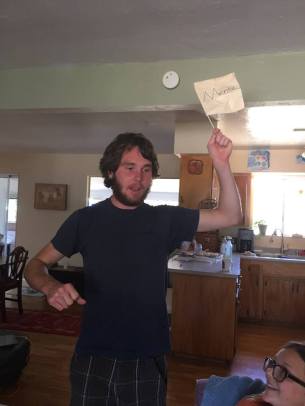

On the other end of the spectrum is my partner, Phoenix. He has schizophrenia and can’t even walk silently into a room without people reacting to his neurodivergence: his strangeness radiates from him like a glow—a beautiful glow, in my opinion, but not in the opinions of most others. He’s one of the very best, coolest, smartest, kindest people I’ve ever met, but most folks will never know that because their reactions to him are almost uniformly negative. They avoid him, or have a (misguided) “protective” anger reaction (for instance, they call the cops on him for yelling and pacing in his yard. They beat the shit out of him for talking to himself, because they think he’s “talking shit” about them). At best, they pity him and don’t take anything he says seriously.

On the other end of the spectrum is my partner, Phoenix. He has schizophrenia and can’t even walk silently into a room without people reacting to his neurodivergence: his strangeness radiates from him like a glow—a beautiful glow, in my opinion, but not in the opinions of most others. He’s one of the very best, coolest, smartest, kindest people I’ve ever met, but most folks will never know that because their reactions to him are almost uniformly negative. They avoid him, or have a (misguided) “protective” anger reaction (for instance, they call the cops on him for yelling and pacing in his yard. They beat the shit out of him for talking to himself, because they think he’s “talking shit” about them). At best, they pity him and don’t take anything he says seriously. want to put out feelers to see what kind of support this idea would have, because it will be a difficult thing to do and I need to know it would have an effect before I set out to do it.

want to put out feelers to see what kind of support this idea would have, because it will be a difficult thing to do and I need to know it would have an effect before I set out to do it.